“How do I help my older striving writers? I don’t know where to start.” As a veteran teacher of writing, Kathy King-Dickman often hears this question from fellow educators.

When students in grades 3–8 are struggling with writing, it can feel overwhelming as we consider how best to help them. In this blog, Kathy models using student writing samples for assessing learning and planning next steps instructionally for older striving writers.

Kathy King-Dickman is a Professional Learning Lead Consultant for Collaborative Classroom and has 30+ years of classroom experience in kindergarten through eighth grade.

Introduction

The first blog in this series focused on analyzing emergent and early learners’ writing. Part two centers on assessing the writing of older students in order to plan next steps.

Although the student writer featured in this blog started off well below grade expectancy, she became a superior writer with just one year of instruction. I hope this will provide guidance and ideas for helping your striving writers – students who may be severely behind in writing.

Working with Striving Writers in Grades 3–8

When we consider student writing from third grade to middle school, in most cases we can focus less on foundational skills and more on the craft and organization of a well-written piece.

Early writers are using most of their energy to get the words they want on paper in a manner in which others as well as they themselves can read them back and make meaning from the marks on the page.

In contrast, when teaching older students, we should be able to shift our focus. We can help older students organize and craft their writing in a way that holds the audience’s attention as well as meets the purpose with the intended audience.

However, as you will see, there are exceptions to this scenario. If our upper elementary students have not been in solid literacy programs with a focus on writing and reading throughout their elementary years, they will lack foundational skills.

Teachers often feel overwhelmed when they look at writing samples from students who are struggling with writing in grades 3 and up. We may wonder what we can do to help older striving writers who are this far behind. Sometimes we fear that it cannot be done. However, this is simply not true!

Meet Our Older Striving Writer

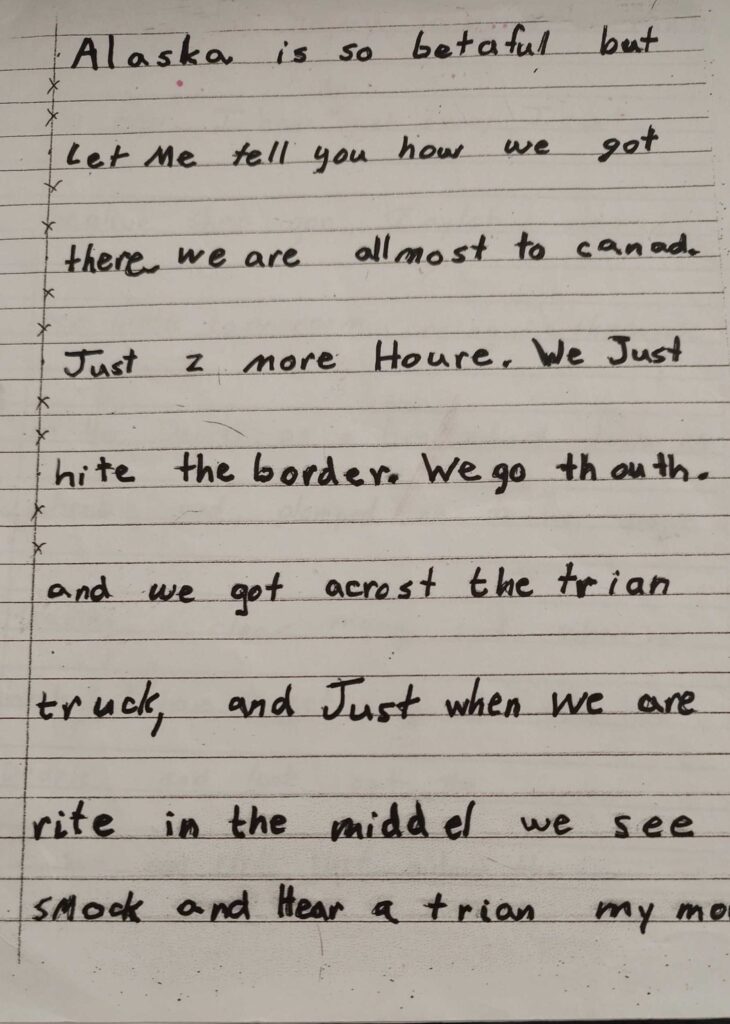

I began working with Maria (not her real name) in the fall of her sixth-grade year. Writing was very slow, hard work for her at this time. Although she worked diligently during every minute of independent writing time, she only completed 7 pages of writing in the first four weeks of school.

Assessing Writing Sample #1

Written during a unit on personal narrative, Maria’s first sample—recounting her trip to Alaska—shows the result of a severe lack in foundational skills. Her 7-page piece was an example of what is frequently called a “bed-to-bed” story. In a bed-to-bed story, the writer crams in every possible detail about an event (from getting up in the morning to going to sleep at night) without discernment about what details are important and memorable, and which are not.

Educators commonly encounter this type of bed-to-bed story when working with young, emergent writers or older striving writers who, like Maria, have had very little writing instruction. Nonetheless, by looking closely at this sample, we can get a clear picture of what this child knows and what she needs next instructionally, no matter where she is in her development.

When Assessing Student Writing, Look at Strengths First

It is important to take a deep look at what skills a child has before we consider what we might teach her next. Here are the strengths I saw in Maria’s sample:

- She seemed to know how to spell several high-frequency words: we, there, is, so, but, just, more, the, go, and, got, when, are, in, see, how, my and mom.

- It seemed that Maria was emerging in her knowledge of where to end a sentence as she had five periods in the correct spot with two missing. Even though she overused capital letters in four instances, she did seem to understand to use them after the end mark of a period.

- Although this bed-to-bed story was developmentally behind, I appreciated how Maria knew how to pull from her life by sharing a very important trip in writing with her classmates.

- Most importantly, I loved how Maria worked so hard at writing each and every day. She listened raptly to my writing lessons, trying all that I taught and modeled, and her pencil never left her page during independent writing time.

Using the Writing Sample to Plan Next Steps

Here are some of the instructional next steps I noted for Maria’s development:

- Clearly the first issue that jumped out as needing work was her spelling. At this point we could have worked on the high-frequency words beautiful, almost, right, across, and hour. I did have her work on the spelling of many high-frequency words as ongoing work throughout the year but lack of time prohibited me from providing her with the deep spelling and foundational work she needed.

- Foundational skills for the ai pattern, silent-e rule, and the syllable –le would also have helped improve Maria’s spelling.

- Another issue I could have taught Maria at this point was the capitalization of proper nouns as seen in the spelling canad for Canada.

- In addition, she overused the conjunction and.

- Improving run-on sentences and fragments was an issue I noted as needing support.

- Maria needed practice in determining the most important or most entertaining details and information to include in her story.

- Finally, writing fluency was definitely a need, though I knew I did not have to worry much about this. I trusted that as hard as she worked, this would come with practice.

Sharing Strengths and Working with Maria

As I mentioned, the first step should always be to name and celebrate the student’s strengths. This applies to all children, but it is especially true for older striving writers.

It can take so much encouragement to get upper elementary students to put pencil to paper. It takes very little for them to simply give up and say, “I don’t have anything to write about!”

Maria was a hard worker and, despite her challenges, was falling in love with writing and reading. I knew that I needed to keep nurturing that love while simultaneously helping her develop many new skills.

Even though the list of strengths was fairly short, I still remember Maria’s look of surprise when I shared it. Maria had been in an ineffective remedial reading program for several years and knew that she was well behind her grade level peers.

The fact that she did not have a good image of herself as a writer but still worked so hard led me to give her only 5 high-frequency words to practice and simply ask her to keep applying herself this year. I promised her that with continued effort during our writing lessons and independent writing time, together we would catch her up.

One Year Later: Maria as a Seventh-Grade Writer

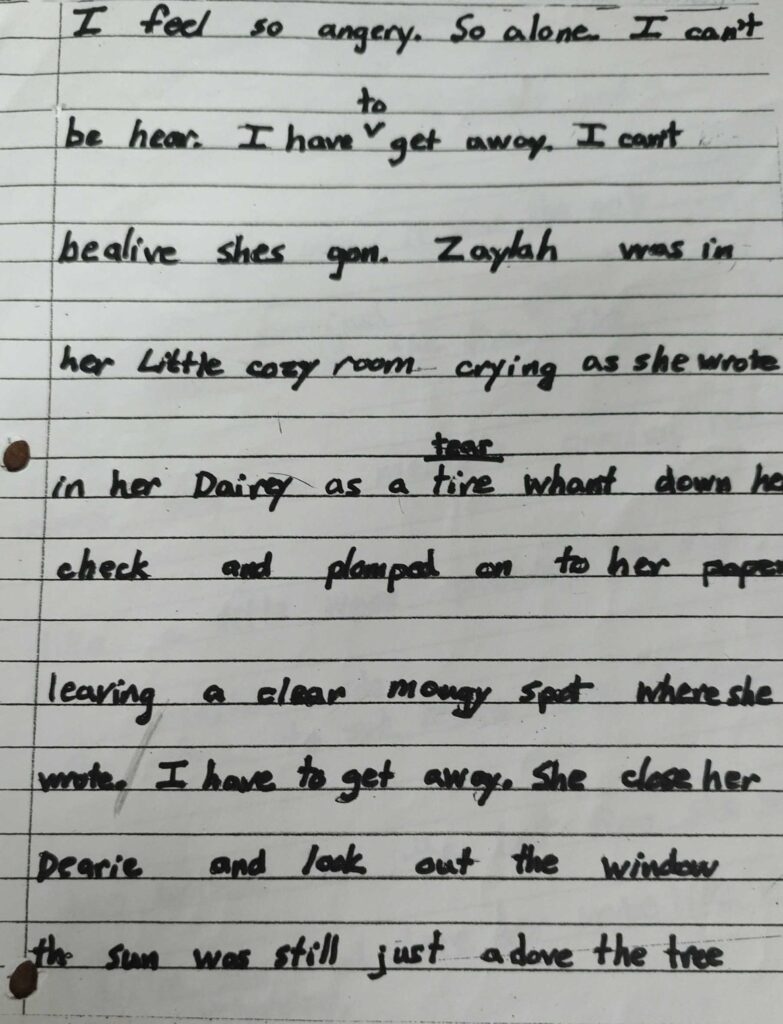

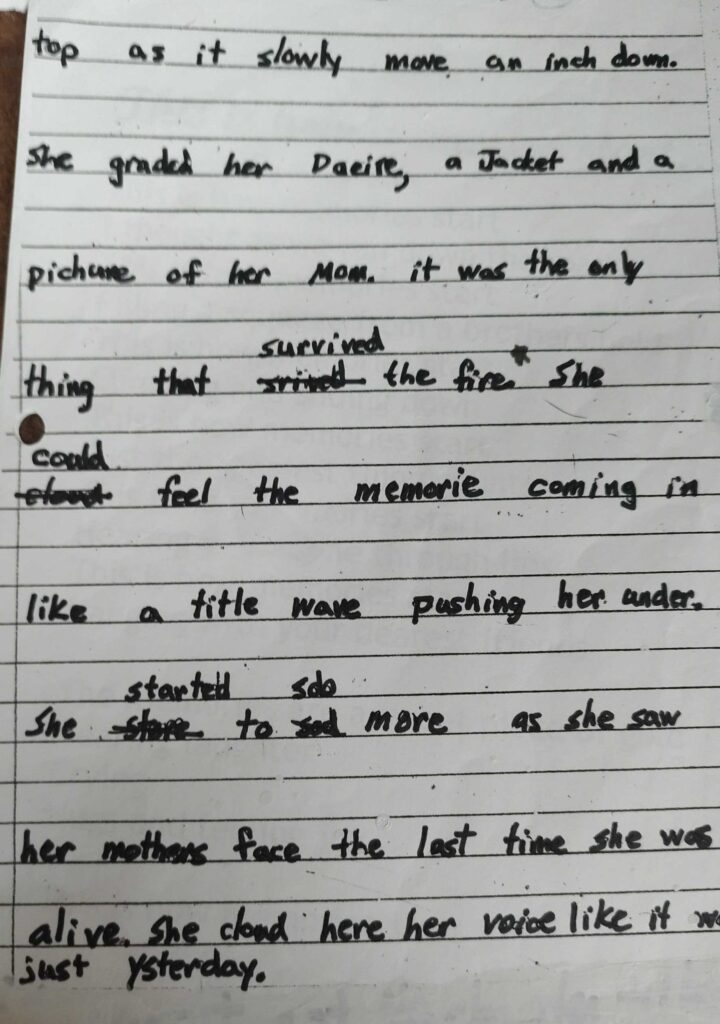

Let’s consider a second piece of writing by Maria. She produced this sample exactly one year after the first writing sample, during a unit on fiction.

Note that the 47-page sample took Maria the same amount of instructional time to write — four weeks — as the 7-page sample she wrote twelve months earlier. This is concrete proof of her huge gains in writing fluency!

I will never forget the day Maria read this completed fiction piece to us. My rule was that if I was conferring with a student and classmates wanted to join us to listen in, they could do so, as long as the writer gave permission. By the time Maria was done reading her 47 pages, the entire class was sitting around the two of us. They were totally silent, with expressions of awe on their faces.

Maria shyly looked up from her notebook and nervously whispered to the group, “I don’t got no chapter titles yet.” Her best friend smiled, leaned close to her, and whispered encouragingly, “It is ‘I don’t have.’ When you write like that, you need to speak the same way!”

The class also had a good laugh on page two of the story, when I interjected “What fire?” after hearing Maria read the sentence, “It was the only thing that had survived the fire.”

Maria looked up, irritated by my interruption, and stated confidently, “YOU will have to wait, Mrs. D. I am foreshadowing . . .” and went back to her reading. What a joy to hear that from a formerly striving writer who was producing short bed-to-bed narratives only one year earlier!

Assessing Writing Sample #2

Celebrating Strengths

In one year of writing instruction—from sixth grade to seventh—how had Maria’s writing developed?

I first considered what strengths I could celebrate in Maria’s second piece of writing:

- It was blazingly clear that Maria no longer wrote bed-to-bed stories! In fact, from reading the entire novelette I could see that she had a solid understanding of the structure of fiction, including vivid characters, a setting filled with sensory images, and a strong plot that kept her audience engaged.

- She also knew to use punctuation for effect; sometimes she even broke rules to do so, as seen in the sentence: “So alone.” This is a fragment and grammatically incorrect but worked well to show her strong voice in writing.

- Other things Maria had control of included: foreshadowing, commas in a series, varying sentence lengths, capitals after end marks, showing character through actions and feelings, and end marks.

- She seemed to have control over the contraction can’t.

- Her spelling had definitely improved even though it did not keep pace with her growth in writer’s craft.

Instructional Next Steps

Maria’s growth was astounding—and she had much left to learn! By assessing the sample, I determined the following possible instructional next steps:

- Although she had misspelled ten words that should have been sight words for her by this point, I only chose five at a time for her to study. I chose could, believe, gone, went and picture as these seemed to be the ones used more commonly in written language.

- She also needed to learn when to double final letters before adding a suffix, as seen in grabed.

- Hear for here showed she needed work on this as well as other homophones. (It is glaringly obvious how much a program like SIPPS might have helped her clear up all of these issues. The fact that she had ten misspellings on just two pages reinforces this fact in a dramatic manner. Another program that would have helped Maria is Being a Reader, Second Edition. The new word study lessons found in the second through fifth grade lessons would have helped clear up so many of these issues before they became problems.)

- The step I chose to work with Maria on was her problem with tense as seen in, “. . . she close her diary.” This was repeated many times throughout this long missive, and is a very common issue with second language learners. Although Maria did not speak Spanish (her mother’s native language) her English-speaking skills were somewhat weak.

Therefore, after sharing all of her strengths, I worked with Maria on five common spellings and proper tense. We reserved the other instructional next steps for other times and other opportunities. Often when we teach more, less is learned.

Reading and Writing Connections: How Avid Reading Helps Develop Student Writing

Finally, it is important to note that our school’s strong Individualized Daily Reading (IDR) program supported Maria in successfully reading 48 novels during that year and the following summer, before she wrote this second piece of writing.

Voracious reading often supports writers, striving or otherwise, and I believe in Maria’s case that this avid reading helped improve Maria’s skills in the area of writers’ craft. Often Maria would find in her independent reading the exact aspects of craft that I was teaching during writing time. For instance, when we were studying showing what a character is like in writing, she found samples of using action, dialogue, thoughts, and feelings that portrayed her characters in her recent novel.

Resources to Determine Appropriate Next Steps

For educators who are implementing Collaborative Classroom programs, here are four places I consult when choosing instructional next steps for a student in grade three and up.

- The first place I look is in the Unit Scope and Sequence for third to fifth grades within Being a Writer. Look in the Table of Contents under Planning Resources in the Implementation Handbook or the Planning Resources chiclet on the Learning Portal. Check both the K–5 Writing Skills Scope and Sequence as well as the Grammar Skills and Conventions Scope and Sequence.

- For a child needing spelling support, another important place to look would be the scope of sequence of the Word Study lessons found in Being a Reader. This can be found in the Planning Resources section of the Implementation Handbook as well as the Learning Portal.

- The last support and probably the most important one is the Conference Records found in the Assessments section of Being a Writer unit Teacher’s Manuals. These can serve as a checklist of what should be included within each genre of writing and are developmentally appropriate for each grade.

Throughout the process, I always make sure I am focusing on the craft of writing and not solely grammar and skills.

So, dear readers, next time you look at a sample of writing and think, “I can never catch this child up,” stop yourself right there. Your older striving writers can grow as much as Maria did.

****

Related Reading

Read part 1 of this blog series: Using Student Writing Samples to Assess Early Literacy Skills