This blog post is coauthored by Angie Neal, a South Carolina speech-language pathologist, LETRS® Facilitator, board member with the State Education Agency Communication Disability Council, member of the ASHA School Issues Advisory Board, and a published author. Angie has presented nationwide on a wide variety of language and literacy topics. Thank you for sharing your expertise, Angie!

Introduction

When South Carolina released its new College- and Career-Ready English Language Arts standards in January 2023, the State Board of Education took a firm stance that mastery of Foundations of Literacy standards is essential for all students. In this blog, we’ll take a closer look at what this means for South Carolina students and educators.

The Importance of Foundations of Literacy Standards

The South Carolina Department of Education states that “If students are not prepared to master grade-level indicators, educators should refer to previous grade-level skills for guidance and instructional support.”

While this is one sentence in a 219-page document, it carries an important significance. This is especially true as educators consider their responsibilities in relation to state and federal legislation. As educators in South Carolina shift to a Multi-Tiered System of Support (MTSS), they must consider the evidence-based interventions they will use to support students who have not mastered foundational skills.

While the Foundations of Literacy standards reflect learning that is expected to be mastered by the end of second grade, many older students experience significant difficulty with these skills.

Teachers in the upper elementary grades may not have as much background knowledge or experience to systematically and explicitly address the needs of students with these gaps.

Teachers in the upper elementary grades may not have as much background knowledge or experience to systematically and explicitly address the needs of students with these gaps. Resource selection and professional learning becomes critically important.

MTSS Implementation in South Carolina

The South Carolina law regarding MTSS is ACT 213, and it was signed into law in 2018. Highlights of the law include the following requirements:

- A data-based problem solving model

- Intervention that is matched to the needs of the student

- Ongoing student assessment

- A layered continuum of supports using evidence-based practices

- Universal screening three times a year for all students in kindergarten and first grade (Students in 2nd grade may also be screened using the universal screening tool as needed for reading difficulties.)

Literacy Instruction in an MTSS Framework

The MTSS framework is an approach to ensuring all students learn to read with a strong emphasis on the need for high-quality core instruction. Focusing on core instruction ensures that students are not misidentified as having a disability due to a lack of robust, differentiated core instruction.

In fact, prior to being determined as having a disability, it must be confirmed that the difficulties are not due to a lack of systematic and explicit instruction in phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, fluency and comprehension. This is because students should not be inappropriately labeled as having a disability simply because they have not been taught the information.

Students should not be inappropriately labeled as having a disability simply because they have not been taught the information.

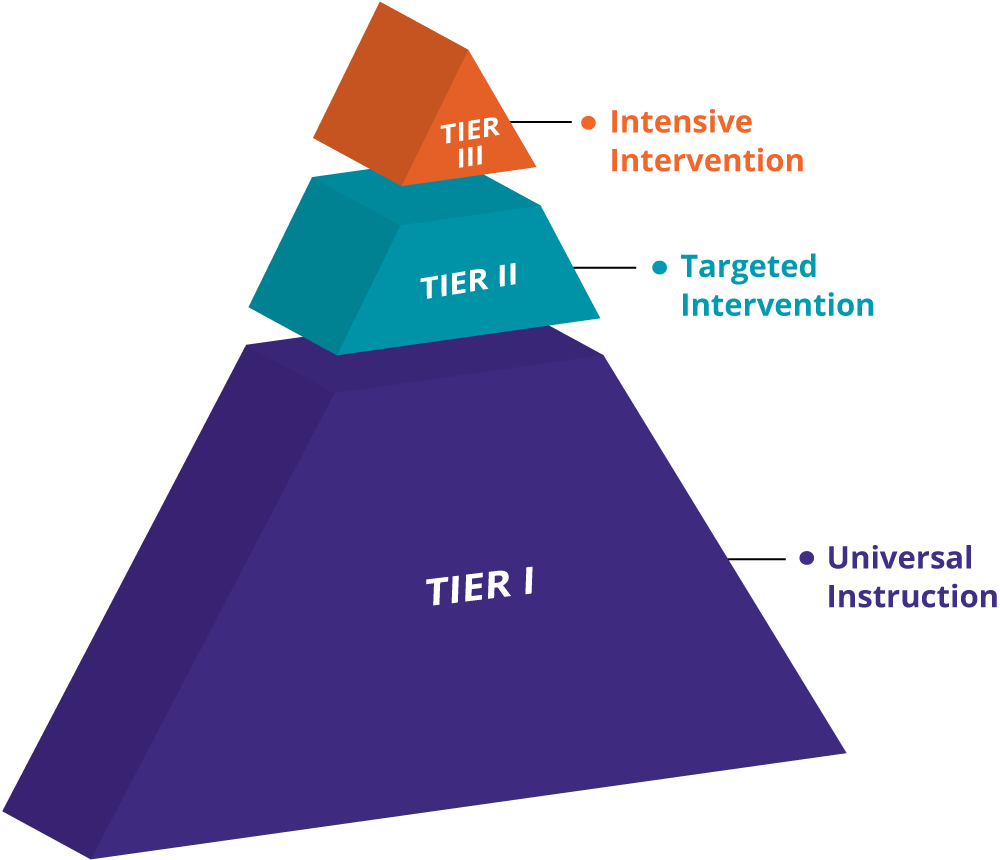

In an MTSS model, core/Tier 1 comprehensive literacy instruction should meet the needs of 80% of the population, and those 80% should be proficient on grade level assessments as a result of core/Tier 1 instruction.

The term “comprehensive literacy instruction” is defined as including developmentally appropriate, contextually explicit, and systematic instruction as well as frequent practice in reading and writing across content areas, which includes age-appropriate instruction in phonological awareness, phonics, decoding, vocabulary, language structure, reading fluency, and reading comprehension (ESSA, 2002).

In an MTSS framework, 80% of students should demonstrate mastery of the Foundations of Literacy standards at the end of each grade level, and they should demonstrate automaticity in word recognition/decoding by the end of second grade.

For the remaining students who need something beyond core/Tier 1 instruction, support is layered through Supplemental/Tier II interventions. This instruction is intended to be a supplement to core instruction, not to supplant it.

In order for students to successfully transfer learning from the intervention to core instruction, supplemental instruction must be systematic, explicit, and aligned with core instruction. Through tiered intervention matched to the needs of the student, the majority of these remaining students should be reading proficiently.

We cannot wait until the end of grade 2 when students are not demonstrating automaticity in word recognition/decoding. Using universal screening and progress monitoring, K–2 teachers identify which students are not progressing toward mastery at the desired rate. They must supplement core instruction with evidence-based practices.

And when we find that a student in grades 3 and above has not demonstrated mastery of these standards, the need for supplemental and intensive interventions is even more urgent. Using evidenced-based interventions that are designed to be systematic, explicit, and accelerative is necessary to ensure these students can access grade level curriculum as quickly as possible.

The MTSS pyramid graphic illustrates how the tiers of instruction work together. It illustrates the research which finds that through appropriate core instruction and supplemental intervention all but 2–5% of students can learn reading skills in first grade even in populations where the incidence of poor reading is very high (Mathes et al., 2005).

Further, only 2–7% of all students identified as being at-risk continue to experience reading difficulties after receiving intensive evidence-based reading intervention in the first two years of school (Mathes et al., 2005; McMaster et al., 2005; O’Connor et al., 2005 Torgeson, 2000; Torgeson et al., 1999; Velluntino et al., 1996).

The tiers of intervention and the instruction provided within the tier must be matched to the needs of the student, because the longer a student goes without getting support for the areas of weakness, the bigger the gap between the child and their peers continues to grow.

Additionally, research findings support the “gap” phenomenon by demonstrating that in kindergarten, the gap can be closed in as little as 30 minutes per day when the intervention targets the specific skill deficits of the student. However, in 1st grade it takes 30–45 minutes a day, in 2nd grade it takes 60 minutes a day, and in 3rd grade it may take 90 minutes to 3 hours a day (Torgeson, 2001).

That said, there is no statute of limitations on learning to read. The same skills a proficient reader needs in beginning instruction are the same skills a struggling reader needs to become a proficient reader.

In fact, after intensive intervention targeting phonemic awareness, explicit and systematic phonics instruction, and practice integrating and applying these skills reading connected texts, 5- to 55-year-olds demonstrated a 17–30 standard score gain in word identification (Truch, 1994).

An Evidence-Based Approach to Foundational Skills Instruction for South Carolina

SIPPS® provides an evidence-based structured literacy approach to foundational skills instruction through explicit instructional routines focused on phonological/phonemic awareness, spelling-sound correspondences, and high-frequency sight words.

Districts across the state of South Carolina are using SIPPS to implement the MTSS framework, whether used as a stand-alone intervention, or integrated to support foundational skills acquisition as a core/Tier I component.

“I used Beginning Level SIPPS with five groups of students during a six-week round of intervention in the spring of 2023. While this was a short burst of instruction, I immediately saw the impact SIPPS has on students,” said Meadowfield Elementary reading interventionist Emma Bell, who used SIPPS as intensive intervention.

Scarlett Mooney, a literacy leader in Beaufort County, South Carolina, whose school is using SIPPS across all tiers, shared, “I can’t begin to express how excited I am to see research, theory, and practice all align. Throughout my career as an instructional leader, the goal has always been to ensure our instructional practices align to research that best supports learning.”

“It has been exciting to watch how direct and systematic instruction impacted all ALL of my second grade readers, not just those identified by MAP scores. By the end of the year, all of my students were becoming far more proficient spellers and readers with a level of confidence I had not seen in years past,” Beth Thompson, veteran South Carolina educator, said about using SIPPS with her second-grade students.

***

Related:

Learn more about SIPPS.

References:

Mathes P. G., Denton C. A., Fletcher J. M., Anthony J. L., Francis D. J., Schatschneider C. (2005). An evaluation of two reading interventions derived from diverse models. Reading Research Quarterly, 40, 148–183.

McMaster, K. L., Fuchs, D., Fuchs, L. S., & Compton, D. L. (2005). Responding to nonresponders: An experimental field trial of identification and intervention methods. Exceptional children, 71(4), 445-463. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440290507100404

O’Connor, R. E., Harty, K. R., & Fulmer, D. (2005). Tiers of intervention in kindergarten through third grade. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 38(6), 532–538. https://doi.org/10.1177/00222194050380060901

Torgesen, J. K., Alexander, A. W., Wagner, R. K., Rashotte, C. A., Voeller, K. K., & Conway, T. (2001). Intensive remedial instruction for children with severe reading disabilities: immediate and long-term outcomes from two instructional approaches. Journal of learning disabilities, 34(1), 33–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/002221940103400104

Torgesen, J. K., & Burgess, S. R. (1998). Consistency of reading-related phonological processes throughout early childhood: Evidence from longitudinal-correlational and instructional studies. In J. L. Metsala & L. C. Ehri (Eds.), Word recognition in beginning literacy (pp. 161–188). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Vellutino, F. R., Scanlon, D. M., Small, S., & Fanuele, D. P. (2006). Response to intervention as a vehicle for distinguishing between children with and without reading disabilities: Evidence for the role of kindergarten and first-grade interventions. Journal of learning disabilities, 39(2), 157–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/00222194060390020401

Truch S. (1994). Stimulating basic reading processes using auditory discrimination in depth. Annals of dyslexia, 44(1), 60–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02648155